History of the Sacrament of Penance

National Liturgical Council

The Sacrament of Penance is sometimes viewed as a very controversial issue in the life of the Catholic Church and also by those outside it. Many of the ideas that people have about this Sacrament are sometimes influenced by distorted views in the media, or misinformation from a variety of sources.

Penance In The Early Church

In the early Church the victory of Christ over sin was offered to men and women through the repentance of their own sins and symbolised through the washing away of that sin in the waters of Baptism, and constantly renewed by participation in the Eucharist. But the Church also had to deal with those who by public acts of sin like murder, adultery and apostasy (renouncing the faith) had cut themselves off from the Eucharist after Baptism.

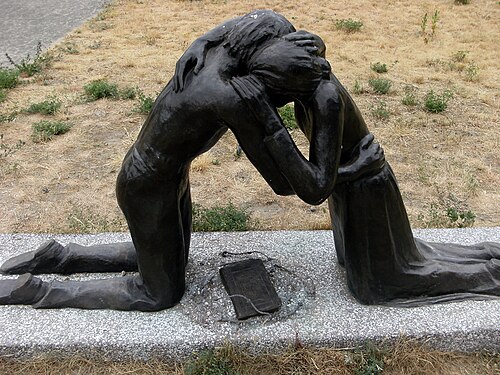

The Church established an order of penitents in which the persons were publicly identified as sinners. Then the whole community became involved in their reconciliation by prayer as the penitents themselves undertook public acts of penance and then they were formally reconciled to the Church by the bishop on Holy Thursday.

This ancient process of reconciliation is mirrored today with our own penitential observances during the Season of Lent. It had however one major drawback. The Sacrament could only be offered once in a lifetime and thus many people even put off baptism until they were on their deathbeds in case they should sin after Baptism!

Celtic Penance

The Church in Ireland in the 5th century was operating differently from the Church in Europe. Rather than being divided into dioceses the Celtic Church was based on thriving spiritual centres of monastic life. Their way of dealing with human sinfulness was not so much a public but a private act. Individuals aware of their sin made confession, undertook penitential acts before receiving absolution. It was very much connected with the practice of spiritual direction and growth in the Christian life.

Its advantage over canonical penance of the earlier period was that it could be repeated. The disadvantage was that this process of reconciliation did not involve the active participation of the liturgical assembly in praying for and supporting the penitent. The understanding of sin also changed with this model. Sin was seen as incurring a debt based very much on the feudal relationship between master and serf and the debt had to be paid off in some way prior to absolution.

The Later Middle Ages

The Irish solution to the Sacrament of Penance became very popular throughout the whole of Europe because of the possibility of frequency, and like the canonical form the Church community could still be actively involved in the process of reconciliation but in a different way to the practice of earlier times.

The debt brought about by sin could be dissolved in either the living or the dead, by applying the fruits of Christ’s own sacrifice. The Eucharist became the instrument by which reconciliation could be gained.

It is from this practice that the custom of having Masses offered for both the living and the dead came into existence. Sadly in some parts of Europe during the later middle ages there were some abuses of this practice – a matter that the Council of Trent looked at after the turmoil of the Protestant Reformation.

After Trent

The 4th Lateran Council that was held in 1215 had made it an obligation that any Catholic who committed serious sin needed to make their confession at least once a year. It was not specified as to when that confession should take place, but Lent became the popular time for confession. Indeed Catholics were encouraged to always go the Sacrament before receiving Holy Communion.

The priest confessor was understood to exercise the role of judge as he determined the penance that should be given to a penitent depending on the nature of the sin committed and number of times that sin had been committed. Penitents underwent a comprehensive examination of conscience in order to determine what needed to be confessed. This practice of the Sacrament of Penance and understanding of it continued up to the Second Vatican Council.

This article was originally published in ‘Healing Ministry’. © Diocese of Parramatta. 2001, 2007. Reprinted with permission.